Metadata fractures - don't let them undermine your work!

An introduction to metadata fractures in an archive - what they are and how you can deal with them

Published on: January 24, 2024

By Tim Manders (Sound & Vision) and Mari Wigham (Sound & Vision).

The Sound & Vision archive contains more than 2 million items (programmes, documents and physical objects) spread over more than 150 years. This represents an enormous treasure trove of knowledge.

Figure 1: Number of archive items per year in de Sound & Vision collection

Users who consult the archive usually have a search question: they want to find material in the archive, such as material by André van Duin. Sometimes, they have a research question, such as “how much material has already been digitised?” , “how often is the word ‘climate’ used during current affairs programmes?” or “which politicians speak most often?”. In principle, the archive should be in a position to answer these questions. However, it is often harder than expected - or even impossible - due to metadata fractures.

What are metadata?

Metadata are data that describe an archive item, such as the title or description. Without these descriptions, it is almost impossible to find something in the archive. Metadata are the lens through which we see the archive.

Metadata have many different sources. They can be entered by programme makers, for example in the form of a title and summary. Metadata can be added manually later, for example an archivist can watch a programme and create a description for it. They can also be automatically generated, such as occurs with the date and time when a file is uploaded. Finally, metadata can be extracted from audiovisual material and existing metadata, for example by recognising people in the image or in the description. Often AI techniques (Artificial Intelligence) are used for this purpose, by training software on data so that metadata can be automatically generated.

What are metadata fractures?

Every metadata source has its own characteristics. A programme maker describes an item in a different way than an archivist, and completely differently than an AI algorithm. Different types of archive items also require a different approach - face recognition is valuable on television material but useless for radio. We call these differences in how metadata are created 'metadata fractures'. These fractures are like scratches on our metadata lens. They cause blind spots and distort our view of the archive.

What causes metadata fractures?

Metadata fractures are caused by changes in selection procedures at archives, and by the use of different methods for creating metadata.

Selection of material

The most fundamental difference in metadata is whether or not an item is present in the archive. An archive doesn't preserve everything. Choices are made as to which material is stored. In other words: a selection is made. Sound & Vision, for example, only archives television programmes if they were produced in the Netherlands. Programmes from abroad are not kept in the archive. An item that is not present in the archive has no metadata. This may seem self-evident, but for users who are not aware of how the selection was made, it can be enormously confusing and frustrating when they don't find what they are looking for.

Different methods of metadata creation

As already discussed, there are different ways of creating metadata. Automatic technology such as AI has the potential to describe much more material than an archivist could ever do by hand, but produces different results. For example, an AI algorithm that uses term extraction could tag a programme with the term ‘climate’ because that word is mentioned many times, whereas an archivist could tag a programme with the term ‘climate’ because the subject is discussed, even if the word itself is never mentioned.

Which metadata are created, and how, depends on the type of the material and the resources available. However, even within a particular metadata method there are many choices that can be made. It is obviously pointless to apply automatic speech recognition to a set design. Using Dutch speech recognition on programmes with a lot of music or other languages is also less worthwhile. Where resources are limited, some types of archive material can be given priority. At Sound & Vision, for example, it is possible to recognise faces in visual material. However, this technology is quite expensive, and for this reason it is only used for material from certain genres, such as news, and only for recognising people who appear often in contemporary media. The use of supporting tools, such as a thesaurus (a controlled list of terms), also has an impact on metadata quality: if names of people are consistently entered using a thesaurus term, then variations in how the name is written don't hinder search. However, due to limited resources, not everyone is listed in the thesaurus.

Figure 2 shows how the availability of subject information for an archive item is strongly dependent on the item's category.

Figure 2: Percentage of archive items with subject information for a number of selected categories

An archive's metadata policy - which methods of metadata creation are chosen and how they are used - therefore has a big impact on the metadata that are created. Sound & Vision came into being from a merger of the broadcast, film, and academic archives. Each institute brought along their own metadata, created according to their own policy. The metadata from each institute contained its own metadata fractures, and the differences between the metadata of different institutes in turn formed new metadata fractures.

Changes over time

Metadata policies change over time, such as when new types of archive items come into being (think of digital and social media), selection policy is changed, new methods of metadata creation are introduced or guidelines are updated. Every change - even if that change leads to better metadata - causes a new metadata fracture.

In the graph below it is clear that newer Sound & Vision archive material contains much less subject information than older material does. This is a result of the transition from manual metadata annotation by archivists to a combination of manual annotation by programme makers and annotation by automatic methods.

Figure 3: Percentage of archive items with subject information before and after 2014

Sound & Vision metadata fractures

The archive of Sound & Vision has a rich history and consequentially also a large number of metadata fractures. To give insight into the most important metadata fractures, we have described these on a timeline in Figure 4. We look at the two causes of metadata fractures (selection and metadata creation methods) in the context of the Sound & Vision archive. We also discuss 'upheavals': moments at which there is a large change that has far-reaching consequences for selection or metadata creation.

The timeline combines all the causes together. Hover over a circle with your mouse to read more about it.

Figure 4: A timeline of metadata fractures at Sound & Vision

NB: The timeline does not tell the whole story, as at any given moment in time there are also differences in how different types of material are handled. For example, in the era of manual annotation, archivists prioritised certain genres, so that some items were given a detailed description, and others a more basic one.

In the following sections we will discuss selection, metadata creation and upheavals in more detail.

Selection

The selection moments (blue circles) represent important changes in the selection policy of Sound & Vision, resulting in metadata fractures. In the beginning Sound & Vision only archives material that is offered to the institute by the producers. In 1970, when the broadcasters start using magnetic tape for archival, the amount of material increases. Regular archival of radio starts in 1977, is extended from 1997 onwards, and since 2006 all public service radio stations are archived completely. Regular archival of TV starts in 1990, and since 2006 all Dutch productions on TV are archived. Both Dutch and non-Dutch music is archived for reuse. Particular effort is made to preserve Dutch music productions. In 2014 Muziekweb takes over archival of music. In 2017 the Dutch Press Museum merges with Sound & Vision, and in 2022 Muziekweb merges with Sound & Vision. Once the metadata from the Press museum and Muziekweb are integrated in the systems of Sound & Vision, new metadata fractures will occur.

Metadata creation

The metadata moments (yellow circles) represent important changes in how metadata are created at Sound & Vision. In 1997 all archivists at Sound & Vision start working with a single catalogue for film, TV and radio. Consistency is further promoted by the introduction of the GTAA thesaurus in 2001, so that archivists use terms from the thesaurus instead of typing in a term themselves, firstly for genres and subjects, then from 2004 onwards also for persons, organisations and locations.

From 2006 onwards, when the amount of material increases due to changes in selection policy, the policy shifts from selecting a small amount of material and describing this in depth, to selecting more material and describing this in different levels of detail. In this way, the limited resources available for annotation are directed more towards material with a higher priority. TV, for which fewer programmes are archived than radio, is typically described in more detail than radio.

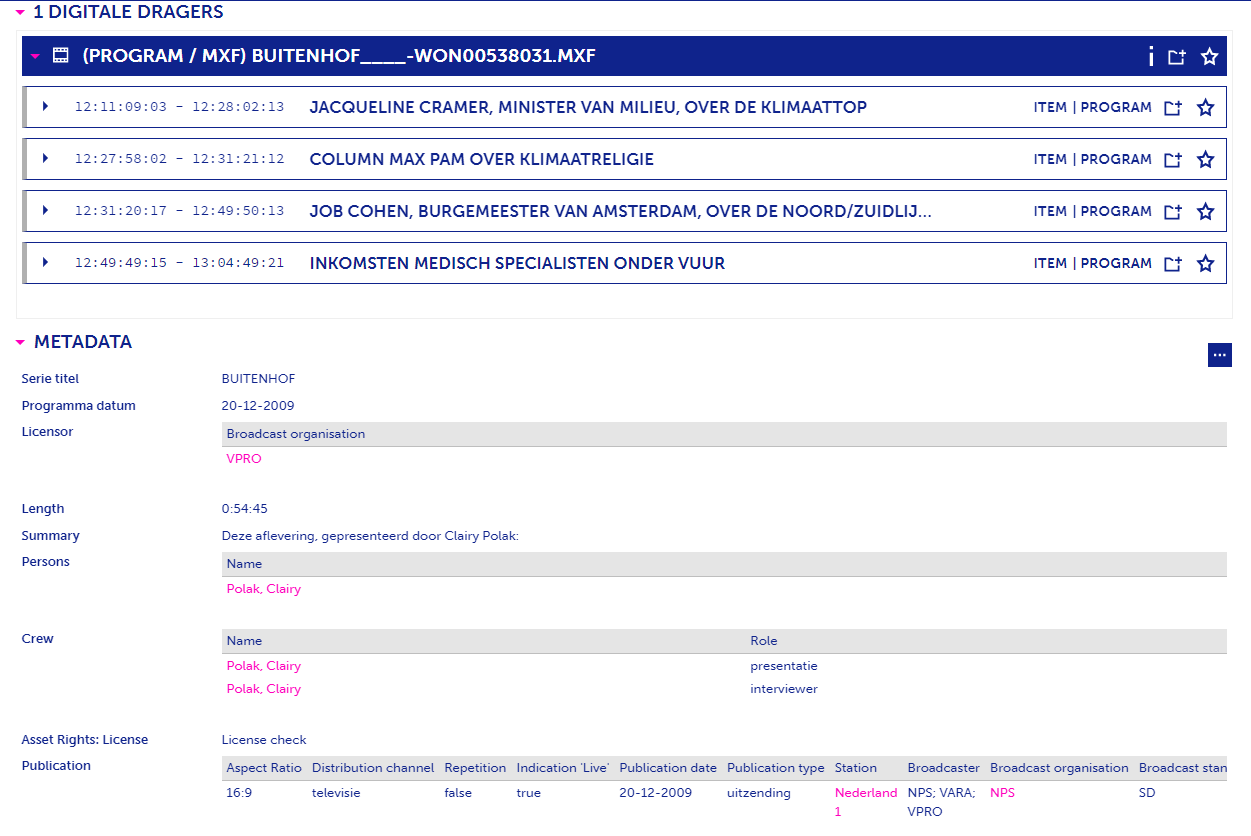

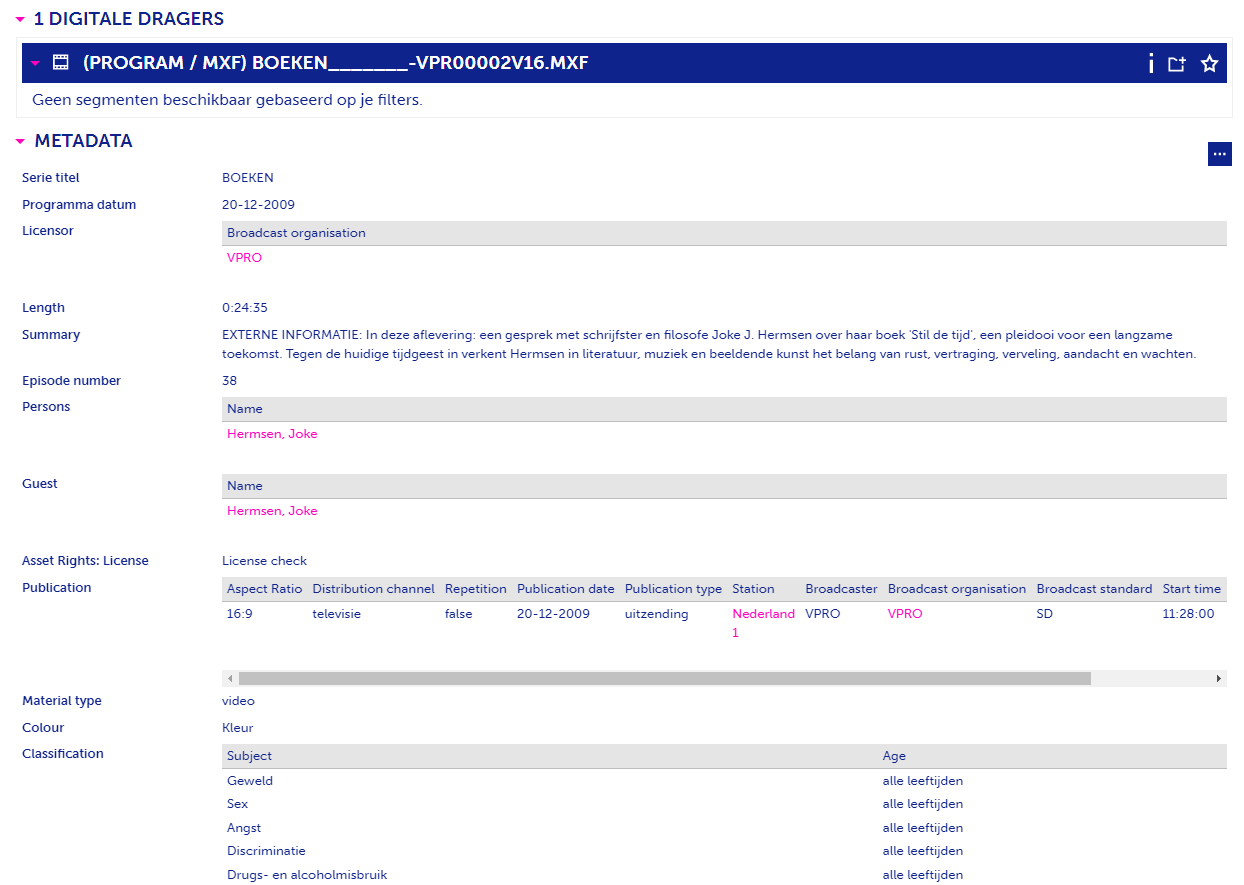

Figure 5 shows two examples of different annotation levels for manual annotation. The first example is an edition of the political programme Buitenhof from 2009. This programme was annotated in detail, including a summary of the programme and information about persons, locations and subjects. There is also technical information, such as the aspect ratio and the programme length. The programme is even split into segments that are described individually. The second example comes from the same year, but is a programme called Boeken that was annotated at a lower level of detail due to its genre. It still contains technical information, but the content information is limited to a single person and a description from an external source.

|

| A programme annotated in detail: Buitenhof. |

|

| The programme is also split into segments, which are also annotated in detail. |

|

| A programme described at a basic level: Boeken. |

Figure 5: Example of different annotation levels

In 2012 Sound & Vision starts the Media Management programme. This is a series of projects aimed at getting better metadata from the source and at automating annotation. It ushers in an era of large changes in metadata, and from 2015 onwards manual annotation by archivists is gradually phased out, in favour of obtaining metadata from the programme makers and by speech recognition (from 2015 onwards) and face recognition (from 2019 onwards).

Upheavals

At some points in the history of Sound & Vision we can speak of an ‘upheaval’, a change that has far-reaching consequences for selection and metadata (purple circles; the dotted vertical lines illustrate the consequences for ‘selection’ and ‘metadata creation’). The introduction of a new metadata management system1 (a software system for entering, storing and searching metadata) in 1997, 2006 and 2018 causes an upheaval each time. The large scale digitisation project ‘Images for the Future' also causes a landslide in the metadata due to the large influx of digitised material.

Impact of metadata fractures

Metadata are the lens through which we look at the archive. Metadata fractures are like scratches on this lens. They disrupt our view of the archive. This has consequences for search and research.

Impact on searching - and finding

Selection has the biggest impact on finding what you are looking for. Of course users can't find material that was not selected to be preserved in the archive. However, users don't know this if they are not familiar with the selection policy. They don't understand why they don't find what they are looking for. Metadata fractures also influence the findability of items. An item with a detailed description, a speech transcript and a list of persons, organisations and locations is much easier to find than an item with only basic information.

Sometimes the information is there, but changes in metadata creation make finding it harder. Look at this example of searching for “Dolf Jansen” in our archive (Figure 6 below). The effects of archive policy can clearly be seen in the findability of items. First the name only occurs in textual descriptions, then as a person in the thesaurus, and only recently in voice and face recognition. Only if users search in all these metadata fields will they find as many results as possible. If they don't know this, they will find much less material than is actually present.

Figure 6: The number of search results per year for Dolf Jansen in different metadata fields

Impact on research

The impact on research is even greater. In order to be able to draw conclusions, you preferably have a complete picture. Where that isn't possible, it is essential to know the limits, to be able to take them into account. Research into which politicians speak in the media, for example, will only find politicians for which there is a speaker model. The researcher must decide whether this limitation is acceptable for their research or not.

Analysis of developments over time is greatly hindered by changes in metadata. For example, information about subjects was previously noted by archivists, now this seldom occurs. Recent material often has subtitles or a transcript that can be searched for a term. However, as previously discussed, there is a considerable difference between the occurrence of the word 'climate' in a transcript and the choice of an archivist to tag a programme with the thesaurus term 'climate'. If a researcher wants to analyse the development of the climate debate based on the number of programmes that discuss the subject, then they need to take these differences into account. For example that relevant programmes may not be tagged, if the programme was not described or the archivist of the time didn't find the subject significant. And that they may count programmes erroneously based on the transcript, if the word climate was mentioned but the programme wasn't about the climate. ('Next week we will discuss the climate...', 'We are not talking about the climate here') or if the word is used in another context ('In the current economic climate'). Researchers who are not aware of these factors will still get results for their analyses. But these results will be distorted by the metadata fractures, whereby the research may draw incorrect conclusions. For example, the conclusion that the climate was not discussed in entertainment programmes in the past, whereas such programmes simply had a lower priority and were therefore described less often.

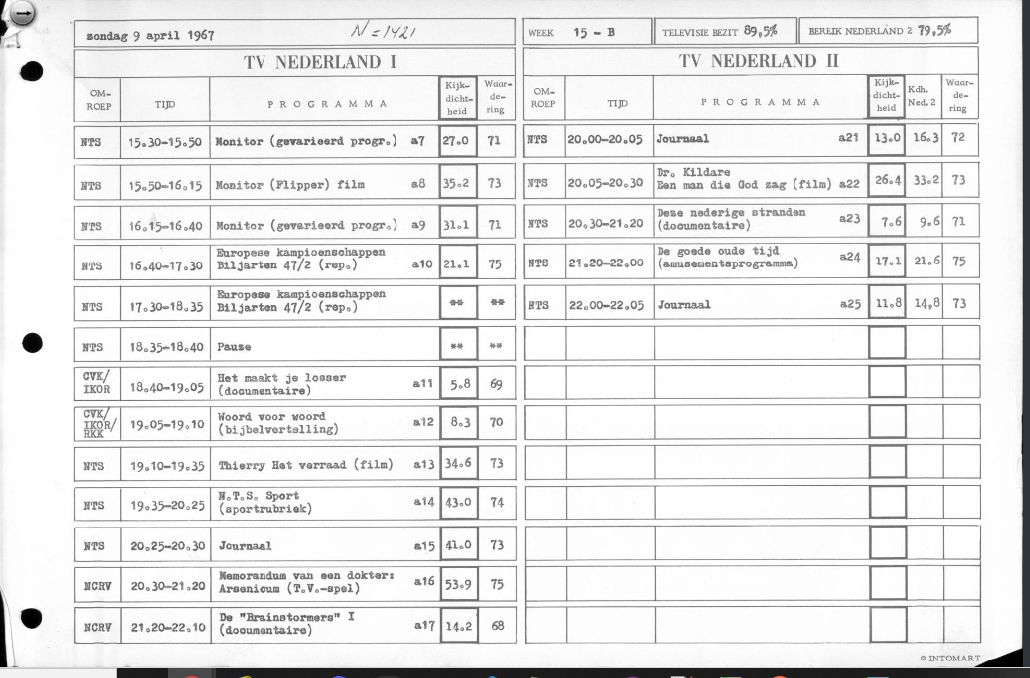

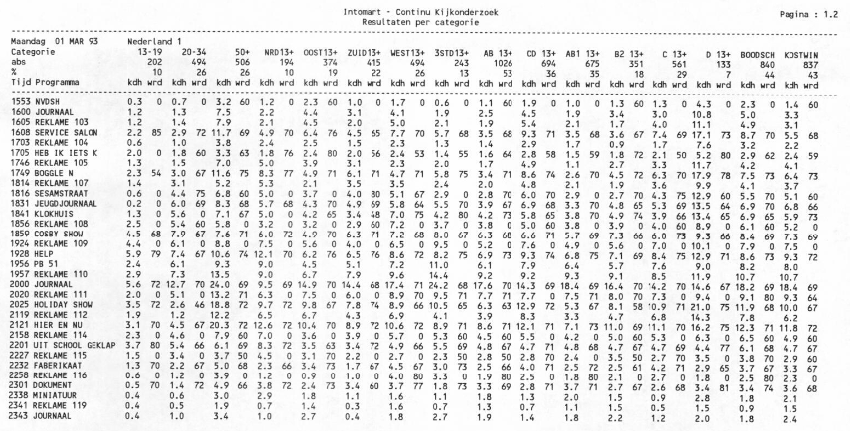

On the occasion of the 70th anniversary of television in 2021 we wanted to analyse viewing and listening figures to identify the most popular programmes. This, however, was impossible. First of all, it turned out that viewing and listening figures were not available for the entire period. In addition, within the period for which figures were available there were large differences in the data structure, and the manner in which viewing and listening was registered changed radically. (see Figure 7).

|

| 1967 |

|

| 1993 |

Figure 7: Examples of differently structured viewing and listening figures.

How does Sound & Vision handle metadata fractures?

This story is part of a Sound & Vision initiative to identify and describe metadata fractures. In this way, archive users can work with the archive in a well-informed manner. Awareness of metadata fractures gives users the opportunity to deal with them in a responsible way, for example by making the right choice of metadata fields or search terms.

How can you handle metadata fractures?

Do you want to search the archive in a better way? Do you want to understand what you do and don't find, why that happens, and how you can take that into consideration? Then the following steps are important:

- Read documentation of metadata fractures (this story is a good start);

- Think carefully about your search question or research question. Which metadata are you using? Over which period of time? Which metadata fractures are relevant for you?;

- Demonstrate awareness of the metadata fractures in the part of the archive that you are (re)searching;

- Investigate whether you can avoid metadata fractures - for example by choosing a different metadata field, searching a more homogeneous subcollection, modifying your question or correcting your analysis results for distortion;

- Use the tools offered by the Media Suite (a research environment for the Sound & Vision archive, among others).

Media Suite tools

The Media Suite gives access to the metadata of a number of important media collections, including various collections from Sound & Vision. In addition, the Media Suite also offers tools to work with this metadata.

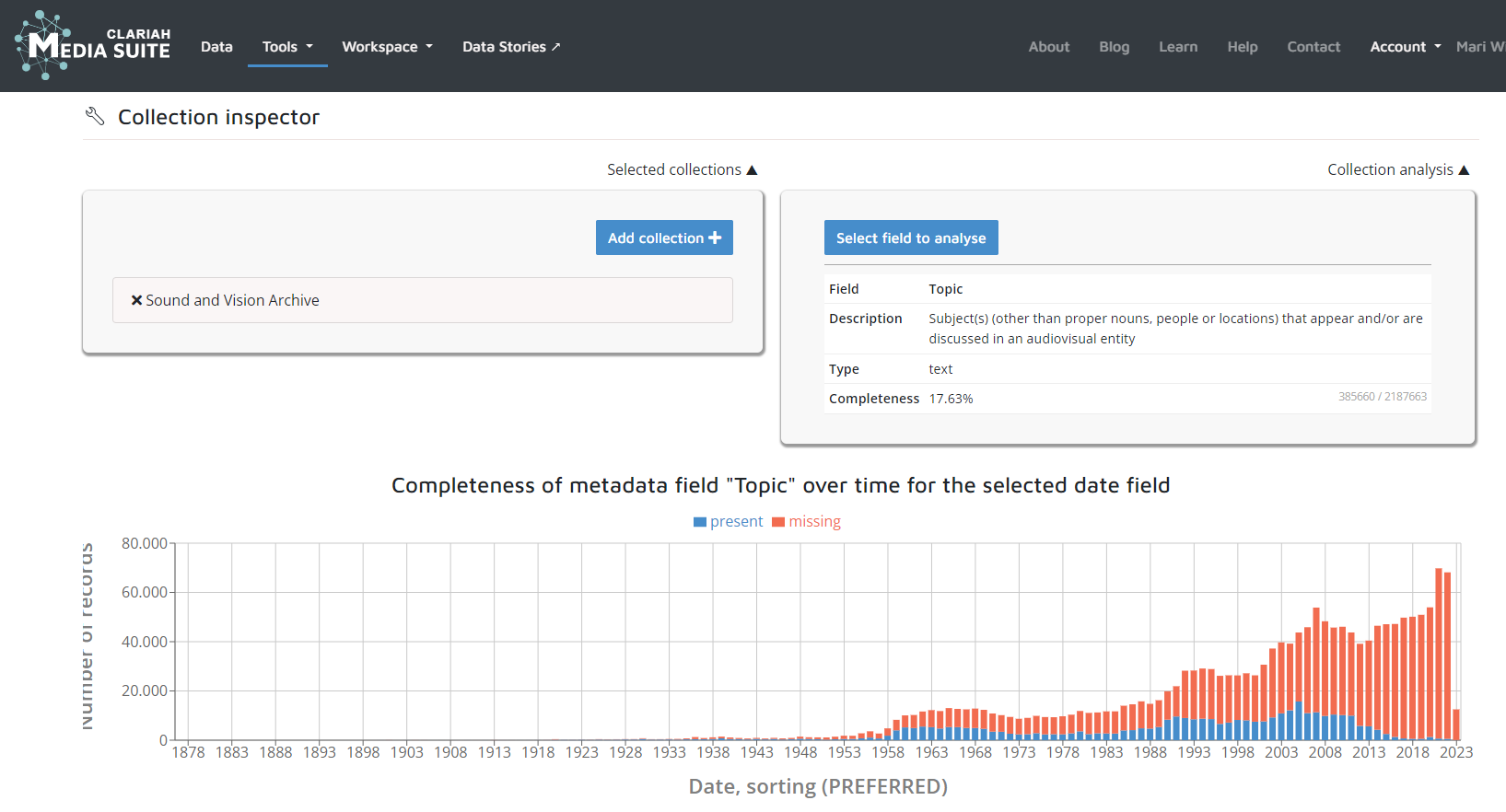

The Inspect tool is available for everyone. This tool shows statistics that help you to find metadata fractures by looking at the completeness of metadata fields, also over time.

Figure 8: Screenshot of the Media Suite Inspect Tool - this clearly shows how the number of items with a subject has changed over time.

Figure 8 above is a screenshot of the Media Suite Inspect Tool that clearly shows how the number of items for which the “subject” metadata field is filled in drops over time.

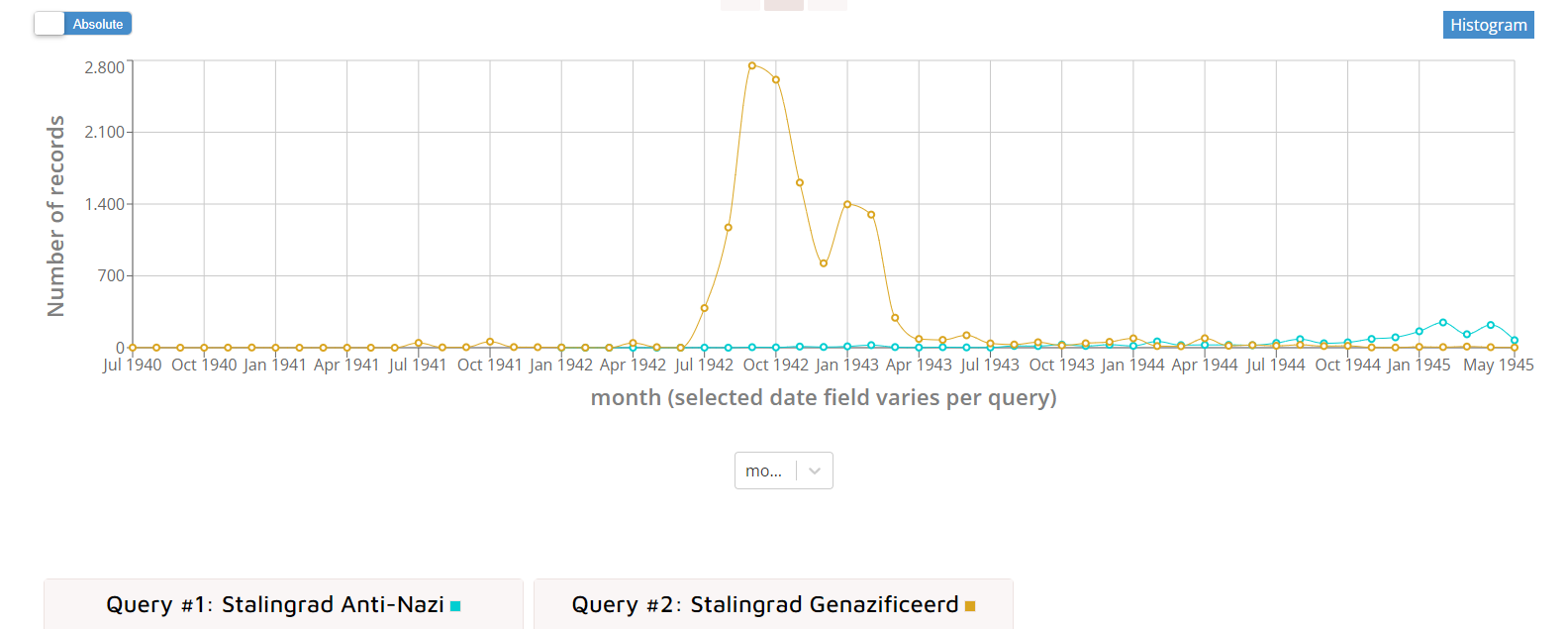

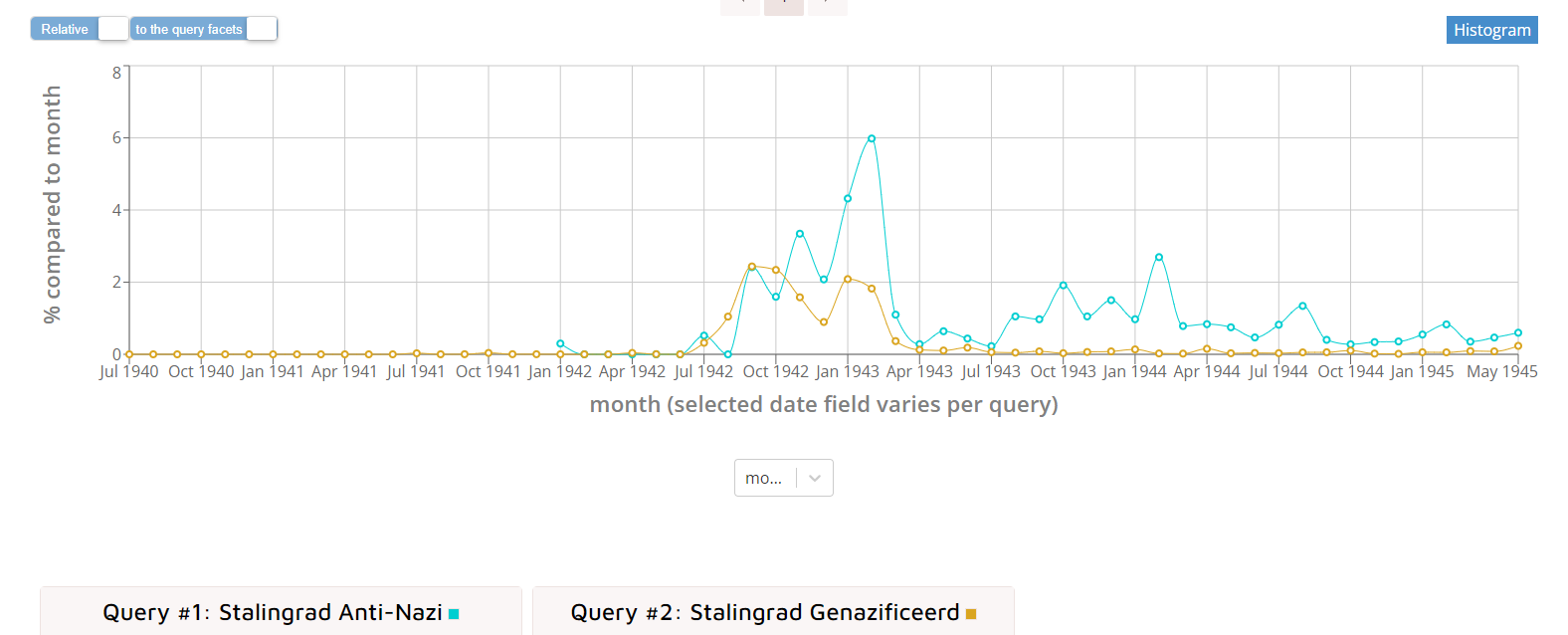

The Compare tool is available for academic researchers and Sound & Vision employees. This tool makes it possible to compare the results of different search questions. In addition, this tool gives you the possibility of compensating for metadata fractures. In this way researchers in the MediaOorlog (Media War) project analysed wartime newspapers in the Media Suite. The newspapers were allocated to the categories ‘Nazified’ and ‘Anti-nazi’. There were many more newspapers in the ‘Nazified’ category than in the ‘Anti-nazi’ category. If we search for ‘Stalingrad’, for example, then the number of newspaper articles with that word is naturally larger in the ‘Nazified’ category than in ‘Anti-nazi’. By looking at percentages rather than absolute numbers, we can compensate for this and we see a very different pattern (see figures 9 and 10 below).

Figure 9: Screenshot of the Media Suite Compare Tool - the absolute numbers of newspaper articles with the term 'Stalingrad' in Nazified and Anti-nazi newspapers.

Figure 10: Screenshot of the Media Suite Compare Tool - the percentages of newspaper articles with the term 'Stalingrad' in Nazified and Anti-nazi newspapers.

Conclusion

Metadata fractures are inherent in a rich and historical archive collection that is growing and developing over time. Ideas about archiving change, new technologies become available and also the wishes of society change. This leads to changes in selection and methods of metadata creation, causing metadata fractures. Some choices have far-reaching effects (upheavals).

As an archive user, awareness is the first step in dealing with metadata fractures correctly. At Sound & Vision we have specific information and tools in the Media Suite to help users to find, understand and compensate for metadata fractures. In this way you can get the best out of the treasure trove of information in the archive.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Vincent Huis in 't Veld, Cor van Veen, Willemien Sanders and Yvonne Peters for their valuable knowledge and feedback.

The Media Suite is developed in the CLARIAH project.

Footnotes

- In this story, we have focused on the metadata management systems of TV en Radio. We will add information about other systems in the future. ↩